900 Views

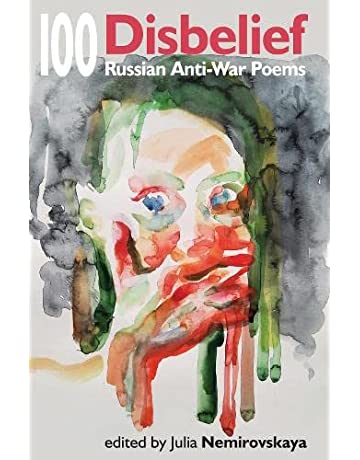

Almost a year has passed since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, but even now one occasionally wakes up in the morning with the eerie feeling of a prolonged nightmare: once I wash my fece andcome to my senses, I’ll realize that everything, the war and all, is just a bad dream. The phase of denial saves the psyche from self-destruction when it is faced with a catastrophe of cosmic proportions. The stages of psychological adaptation begin with a sense of unreality – hence the title of the bilingual anthology “Disbelief “, published by the U.K.’s “Smokestack Books” and edited by Julia Nemirovskaya. From the first weeks of the war, Nemirovskaya began to collect poems in the “Kopilka” (“The Piggy Bank”), a project that continues to this day. The project became especially important for poets in Russia: not being sure of their own safety, they hurried to transfer poems to Nemirovskaya for safekeeping. The anthology contains just a fraction of all collected material. The cover art by Maria Kazanskaya prepares for immersion in the period of initial shock that’s so characteristic of the first half of 2022 (there are a mouth covered by the hand, the widened eyes, the facial expression “this can’t be happening”). Seventy poets and five brilliant translators, Dmitry Manin, Maria Bloshteyn, Anya Krushelnitskaya, Andrei Burago and Richard Coombes materialize, adorn in words the unreality of the unbelievable.

War is an elephant from the parable. A hundred poems, like the proverbial seven blind men, reach for different parts of it and try to determine for themselves how to live next to death, betrayal, blood, lies. What the authors were able to find depends to a large extent on their angle and on the location vis-à-vis the bloodshed. Some watch their news feed – and the current events get divided into genuine and falsified, into official news and smuggled through the VPN:

his sister writes him on whatsapp:

why don’t you finally open your eyes

and look at what the head of its own fsb writes

he can’t be lying, he’s state official after all,

and she pastes a long quote

and he answers her:

wait a minute, why can’t he be lying?

and she sends him a gif from the film volga-volga

and then a quote by lukashenko

(Ksenia Buksha)

Others look in horror at the faces of people they had considered relatives or compatriots:

I’ve abandoned you to your houseplants in Babushkino.

You look out of the window, then back into your ape got screen.

What more do you need to believe that this is a war?

Cargo 200 boys? There’ll be many of them on your street.

Eat their dead heads, clomp down to the church of onion chaff,

Kiss the wrought-iron frames ’round the faces of saints till you swoon.

Love and revenge tear at me and split me in half.

I cry in the day, but at night I sharpen the deadly blade of the moon.

(Julia Nemirovskaya)

Some reassemble themselves bit by bit in forced exile, in evacuation:

We’ve been strewn through the cities of Europe.

The cities delight, but within them we’re strangers.

Back home, missiles are flying non-stop.

Girls weave camouflage, young men dig trenches,

While down in the basements, huddles my generation.

Winds of the war tear us like leaves off our branches.

(Boris Khersonskij)

Some are trying to find a niche where they can become of use, to determine own role in what is happening:

But now the Lord himself has taken thought

To raise me up far higher than before.

I am today a pixel, safely caught

And granted life on glass shattered by war.

(Vadim Groisman)

A group of ten people, many of them are deaf.

A volunteer from Pakistan is not sure to whom the ticket should go.

-To that girl over there.

-But she’s only twelve!

-I spoke to her, she’s more adult than us, bro!

Oh Lord, here I stand, wearing all white,

Wearing the useless white, in the rear lines of Good.

Please, later on give her back some of her childhood,

Give her back, dear Lord, what was taken away in the fight.

(Aleksander Lanin)

But each of the authors presented in the anthology – suffering, not believing their own eyes, angry, helpless and helping – is experiencing both a personal catastrophe and a personal transformation. The vast majority of the authors included in the anthology today are outside of Russia. And this is just the chronology of the first year and the first half of this year!

Getting into a polemic with the famous Adorno’s phrase, the poets in search of new expressive means get united in a choir. During the presentation of the anthology, Julia Nemirovskaya pointed out the value of the choir – a choir of poetic voices a la Greek tragedy, mourning multiple deaths and blaming the perpetrators, a choir that takes moral responsibility for the deeds it witnesses. When such a chorus—a superego that denotes a framework, a moral imperative— appears on stage, it means that the power of the collective mind is being put forward to counteract the amorphous, all-pervasive Evil. Gradually, we overcome the shock, we begin to choose the words that line up on the paper, forming moral barriers, and the form naturally adapts itself to the content.

The anthology is systematized alphabetically, but as one reads poems one after another, the core ideas gradually appear, an emotional canvas is woven, which in itself becomes evidence worthy of a war correspondent. One defining emotion is internalized guilt:

The Holy Spirit rides the sunrise, making houses cheerier.

I’m cracking macadamia at home in my Siberia.

This could be a nanorobot, or a balding dick, again.

There’s your Europe, cut your window, use your trusty VPN.

There’s your Europe, cut your window – ante-loping, anti-door.

This may be a shitty rhyme, since it is not about war.

(Olga Gulyaeva)

Punish us, merciful Lord, punish us,

Lead us into dark alleys and make us eat dust,

Show us the shiv, plug our pieholes,

All the same, we have no spirit, no soul.

(Ksenia Kazantseva)

Another, no less painful, all-consuming is powerlessness:

In the darkest times, neverthecursed before,

All you can think is this: war, war.

All you can do… not a damn thing anymore.

(Lena Berson)

Yet, anger already raises its head:

Strolling trolls, playing oom-pah-pah,

Stomp upon our souls, pounded raw.

They pull bestial faces. We sit

Low, we , like trampled moss, grow.

-What’s the monstrous pit?

-Moscow.

-Step away from the edge of pit.

(Dmitry Kolomensky)

Anger often transcends to an action. Anger leads to battle, and even now, when the hopes for resistance within the Russian Federation have been almost entirely dispelled, and almost all dissenters have been suppressed, annihilated or exiled, its individual manifestations mean that the Russian people are not completely broken, that the identity of a Russian will someday be able to revive, albeit outside the country.

We cannot remain silent about self-deprecation as a new way of mental survival, which arises in many of the poems:

I’ve lost my right to have a voice, a vote,

Or even mingle in the conversation.

(Evgeny Klyuev)

Yuri Gugolev washes every morning stains of indelible blood, not unlike Frida’s handkerchief:

But with all the scrubbing and scouring

It stayed, spread to my skin, everywhere.

And the salty taste of iron

In the sky, on my lips, in the air.

Tatyana Voltskaya asks forgiveness of the desecrated medals of her grandfathers:

I hold them in my hand,

And say, I’m sorry.

Grandad Ivan was a doctor

In blockaded Leningrad,

At a military hospital. I wonder

What he would say to our rocket thunder

On Kyiv…

For post-Soviet people, this is a second strike, opening the old scars; this is as close as one can get to the traumatic, irrationally destructive nature of the war. The self-deprecation of those who find themselves on the team of Evil is much more intimate than the public admission of one’s own guilt. Will the deep-imprinted sense of self-inadequacy heal in this generation?

It is important to say a few words about the translators and the titanic work of the heart and mind that these texts demanded. The translations are made with the greatest care, preserving not only the form and style, but also the emotional component, with the precision of a tuning fork, allowing for the co-tuning of the entire book, so that it sounds like an orchestra. It is thanks to them that the English-speaking public will be able to fully empathize, grasp the scope of the, so far, unending catastrophe.

Try to read them in order of appearance, page by page, and a feeling of overheard confession will creep in, so personal are the poems in this anthology. It is the autobiography in the making; each separate voice in the choir serves as the inner core on which the experience of war is built. We have yet to live and find the expressive means for what awaits us in the second year of the war, and to gather the moral strength for the next stage, the heroic one. And already the voice of hope appears out of shame and darkness:

while the war unfolds like a thunderstorm

we keep pouring from hand to hand

the cold inglorious water of love

we say to it:

sprout from the past

sketch the lines of out future

while the present’s eyes are poked out

while our heart has fallen

in a remote well, to its very bottom

and we have no way of reaching it

we keep pouring from hand to hand

the cold inglorious water of love

(Tatyana Vinogradova)

As of today, great many are scarred and scattered. “Woe to the shepherds who destroy and scatter the sheep of my pasture!” – this is a quote from Jeremiah, not from the anthology. Yet, going back to the collected poems, maybe something important, something that will survive the ruin of intellectual and emotional pastures, may hatch in this inanimate frozen-through water. Is it possible that this group effort to atone for the guilt of innocent language, a group cry for lost innocence, will open up certain apertures, cause a wave, a public outcry, and rock the silent? Could it be that the new Russian poetry will humanize Russians and stop the bloodshed? Don’t call me naïve. It’s imperative to hold on to the dream. Don’t we all need to do something?